Using ElasticSearch as a super fast structured data storage in Populate projects

ElasticSearch is probably the preferred full-text search engine nowadays for most developers: it’s fast, powerful, comes with nice defaults that just work, and the ecosystem of tools around it is growing really fast.

Lately, developers are starting to use it as a data storage too, mainly for logs (storage and analysis). We, at Populate, have been using it for months as the main data repository for our projects and the results are really satisfactory.

Some of our favourite features

-

JSON format by default. Everything is stored as a JSON document, and returned in the same format. It’s a format we are happy to work with in the front-end and the backend. Also, having to transform the data from other not-so-friendly formats such as Excel, Access or XML is a good opportunity to clean it, and change its internal structure.

-

Schema-less documents. The world is complex, and the data too. Each kind of data has its own peculiarities: some data is flat, other is structured, some are represented as numbers, others as strings. We need to define an initial schema and iterate it while we evolve our applications.

-

Security and replication. ElasticSearch clusters are almost transparent to the user, and they provide performance, scalability and security without investing much effort on complicated setups.

-

Fast. We are still impressed how a query across more that two million records with multiple filters can be executed in less than 50 ms.

How we work

For each dataset we want to import in ElasticSearch we follow this process:

- Identify the variables and the dimensions: variables are the candidates to be displayed per se or as the result of an operation (e.g. the average) and dimensions are used to filter the data.

- Define as many schemas as we need. We normally to work with a generic JSON schema that evolves from this format (of course the types can be different):

(Note that, for better performance, we configure the variables as “not_analyzed”)

To evolve and validate the schemas, we study the different queries required on each page. You need to bear in mind that there isn’t an equivalent operation to the JOIN in SQL, you might need to update the list of filters required as your project evolves.

In order to update your existing indexes, it’s important to provide an ID for each document stored (and also to avoid duplication). Thanks to the master-slave configuration you could remove a node to update the schema while the application is working with the rest of the cluster. Once all the schemas have been updated, you just need to promote the updated node as master, and let the others replicate the information from it.

Once we feed the indexes with some custom scripts we add a small layer on our application in front of the ElasticSearch to add security and to transform the input data (parameters) and the output data (maybe adding some meta information).

Use cases

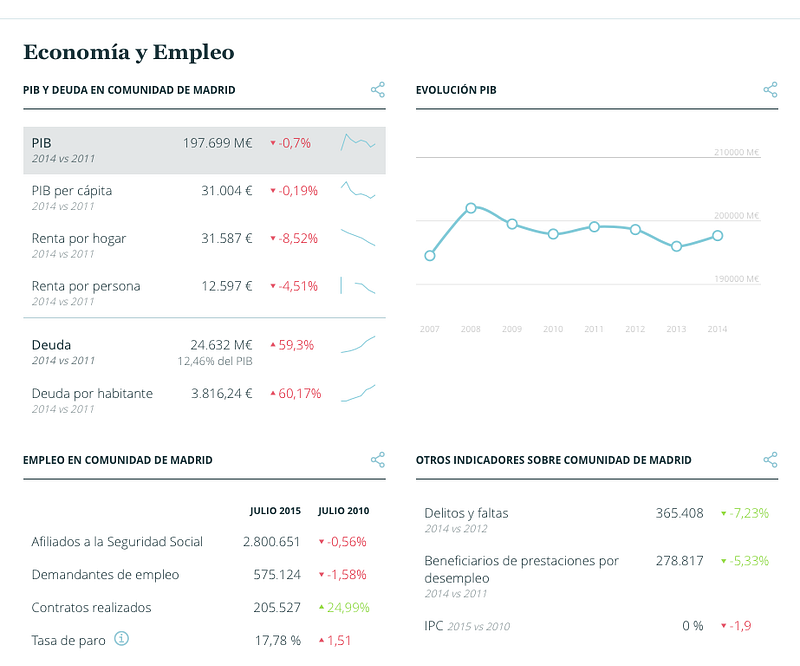

España en Cifras

As we described in the post about the process, the project consisted on displaying more than 85 different datasets in a friendly way. Storing those datasets in a relational database can be really complex, because it requires to create a schema different per dataset, or to unify all the datasets under a single schema with the same types. We quickly discarded the relational database option because the diversity of the data.

Therefore, we created one ElasticSearch index with many types, one per dataset, with the same schema but with different types (to accommodate numeric and text data). Each of those 85 types are an independent data source in JSON format that different widgets on the page queried to compose the pages. We just added a simple API in front of it for convenience.

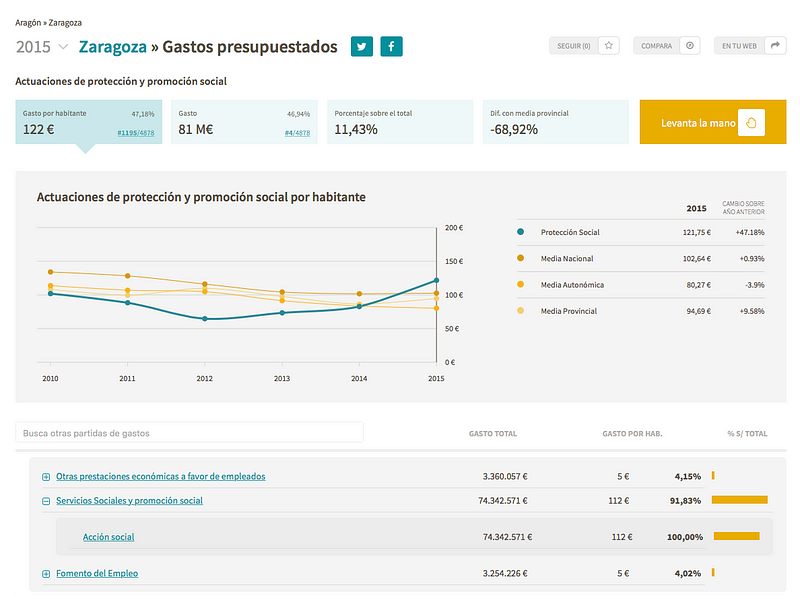

Gobierto comparador de presupuestos

Our local budget comparator tool presented different challenges than España en Cifras: it was only one dataset instead of 85, but the amount of data was far bigger. And, we needed to aggregate data (means, percentages, variations) across multiple filters (population, location, etc). All these calculations can be stored as pre-calculated data or can be performed in real time. The problem of storing it as pre-calculated data is the amount of different combinations required to represent all the possible filter choices, so real-time was the only option.

Thankfully, in version 2.0 of ElasticSearch the performance of calculations and aggregations was improved significantly. If you check the speed of the site you’ll see how even the more complex calculations are resolved in milliseconds.

Conclusion

We make heavy use of ElasticSearch and we are very happy with our choice, because it lets us to create fast applications that we can iterate quickly with the confidence that the data storage will be able to adapt to the new requirements.

In the next months we are considering the idea of gathering all of the public data we currently use in different projects under a single, all-encompassing, kick-ass data platform. But that is the subject for another post